Our research focuses on the design and analysis of quantum algorithms, with an emphasis on near-term applicability and connections to the natural sciences. We develop methods for device-independent certification, explore the structure of Bell correlations in many-body systems, and work on the theory and implementation of tensor networks. Additional interests include quantum machine learning, entanglement theory, and broader contributions to the quantum information community.

Our vision is to make real-world quantum computing practical by integrating theory, experiment, and applications. Our research efforts are embedded into the Applied Quantum Algorithms – Leiden initiative, a collaborative effort to advance quantum technologies through interdisciplinary approaches.

Our work in quantum algorithms spans hybrid techniques, eigenstate preparation, and quantum-enhanced solvers for continuous problems. We aim to balance algorithmic expressiveness with resource efficiency, addressing challenges posed by near-term architectures.

Ground-state preparation. We proposed a general-purpose quantum algorithm to prepare ground states from a trial state, building on recent advances in solving the quantum linear systems problem. Our method achieves exponential improvement in precision and reduced ancilla overhead compared to phase estimation, making it especially appealing for early quantum devices1 .

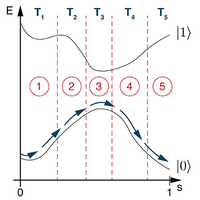

Adiabatic spectroscopy and variational methods. We introduced a hybrid algorithm combining adiabatic evolution with variational optimization. The method yields spectral information and reduces total evolution time, making it suitable for systems with limited coherence2 . This approach has found use in recent experiments with Rydberg atoms. A related strategy based on echo verification was later proposed to mitigate coherent non-adiabatic transitions3 .

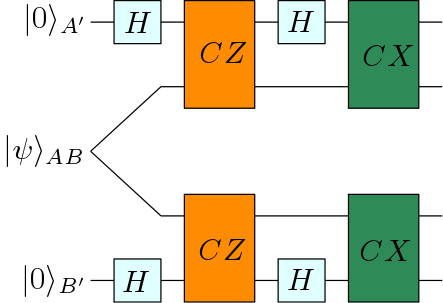

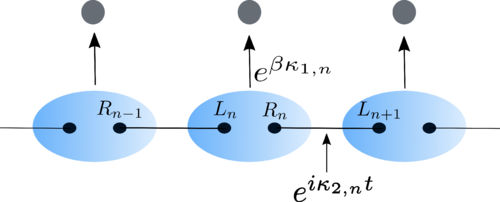

Quantum algorithms tailored to distributed architectures. We proposed hybrid methods to prepare low-energy eigenstates efficiently in networked or modular quantum devices. Notably, we developed techniques that leverage a coherent link to improve eigenstate preparation4 , and introduced a distributed protocol for preparing low-variance states5 . These developments are inspired in part by our contributions to the SuperQuLAN project.

Quantum differential equation solvers. We extended variational techniques to solve both ordinary and stochastic differential equations. This includes an analysis of VQAs inspired by Runge–Kutta methods6 , and a continuous-variable quantum algorithm for solving ODEs7 .

Quantum algorithms for near-term devices. We contributed to algorithm design for NISQ-era platforms, focusing on reducing sampling costs and enhancing parameter tuning. This includes optimal parameter shift rules8 and SDP-based noise mitigation for overlapping tomography9 . A broader perspective on these challenges and opportunities was laid out in our early programmatic work10 .

Shallow circuits, divide & chop. We investigated shallow quantum circuits as approximators for complex quantum processes11 , studied multi-basis representations12 , and analyzed circuit-cutting bounds13 .

We develop methods to verify quantum states, devices, and correlations in a device-independent fashion. This includes techniques for self-testing, randomness certification, and entanglement depth estimation, all relying only on observed statistics and minimal assumptions.

Self-testing protocols. We contributed to the development of self-testing techniques for certifying quantum states and operations based solely on observed outcomes. This includes the SATWAP inequality for maximally entangled states16 , robust self-testing of quantum assemblages17 , and approaches based on mutually unbiased bases18 and graph states19 . We also contributed to the generalization of SATWAP for GHZ states of arbitrary local dimension20 .

Entanglement depth certification. We devised device-independent witnesses for certifying entanglement depth from two-body correlators21 , along with optimization techniques to enhance their robustness22 . We also studied the Bell correlation depth in multipartite systems23 .

Randomness certification. We study the certification of quantum randomness in device-independent and semi-device-independent settings, identifying the minimal quantum resources required for secure randomness generation. We showed that in multi-input/output Bell scenarios, Bell nonlocality is not always sufficient to certify randomness, establishing a separation between the two concepts24 . We also provided necessary and sufficient conditions for randomness certification based on measurement incompatibility structures, linking randomness generation to hypergraph properties25 . Early ideas on the relation between randomness and nonlocality were already explored through monogamy constraints in non-signaling theories26 .

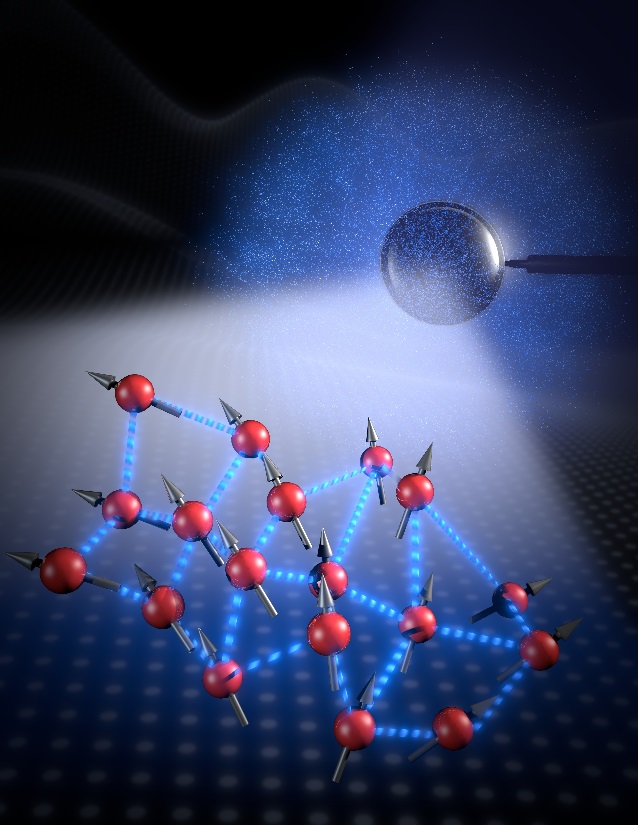

This line of work began during my PhD29 and remains a cornerstone of my research. It seeks to characterize and detect Bell correlations in large quantum systems using accessible observables such as low-order correlators or the energy. These correlations defy explanation by local hidden variable models and underpin device-independent quantum information.

Few-body Bell inequalities and experimental detection. We introduced permutationally30 31 and translationally32 invariant Bell inequalities built from one- and two-body correlators, laying the foundation for scalable detection schemes. These methods enabled the first detection of Bell nonlocality in many-body spin systems, including a Bose-Einstein Condensate of 480 atoms and a thermal ensemble of 5×105 atoms. More recently, Bell correlations were observed in spin systems beyond the Gaussian regime33 .

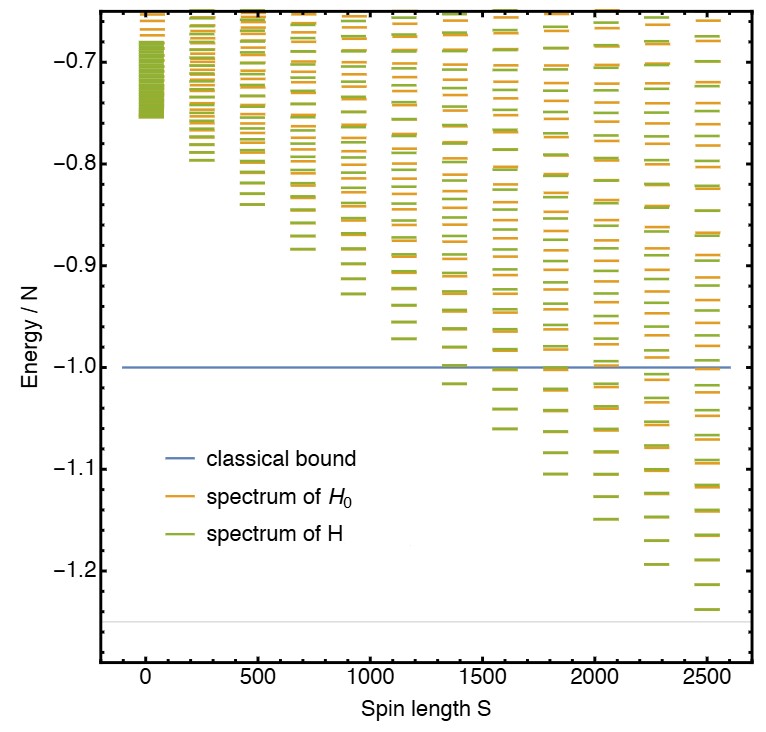

Energy-based Bell witnesses. We showed that the ground state energy of certain spin Hamiltonians can serve as a Bell witness, enabling detection of nonlocality through energy measurements34 . The technique leverages convex optimization and dynamic programming for tight classical bounds. More recently, we proposed new optimization tools based on tropical algebra and tensor network contractions35 36 , studied topological effects on Bell nonlocality37 , and developed strategies for operator bouncing between Bell operators and inequalities38 .

Semidefinite relaxations of local sets. We proposed a hierarchy of semidefinite programs to approximate the set of local correlations from the outside, enabling benchmarking of experimental data against few-body permutationally invariant Bell inequalities39 . These tools become indispensable when tackling richer scenarios, such as those with more outcomes or higher dimensions. We extended this framework in a tutorial on deriving three-outcome Bell inequalities40 and applied it to dimension witnessing and spin-nematic squeezing in many-body systems41 .

Temperature and quantum chaos. We showed that Bell correlations can persist at finite temperature in spin systems with infinite-range interactions42 , with spin-squeezed states as optimal witnesses. More recently, we proposed a Bell inequality for three-level systems and linked its violation to suppressed spectral signatures of quantum chaos43 , highlighting connections with random matrix theory; a work we dedicated to the memory of Fritz Haake.

Preparation and certification. We explored protocols for the adiabatic preparation and verification of tensor network states in quantum devices44 . Our approach provides efficient semidefinite programming tools to certify spectral gaps along the adiabatic path and introduces a complete set of verifiable observables for scalable fidelity benchmarking in many-body quantum simulations.

Adiabatic preparation and gap engineering. We developed a method to maximize the spectral gap in adiabatic protocols by optimizing over parent Hamiltonians, enabling faster preparation of tensor network states without altering their ground state45 . The approach applies to both injective and non-injective tensors and is demonstrated on paradigmatic examples like the AKLT and GHZ states.

Spectral gap certification. We introduced a hierarchy of semidefinite programs that yield rigorous lower bounds on the spectral gap of frustration-free Hamiltonians in the thermodynamic limit46 . Our method generalizes and improves upon existing finite-size bounds, offering tighter certificates and extending the regime where a gap can be provably detected.

Training strategies and optimization. We evaluated noisy training via density functionals49 , aiming to understand and mitigate the challenges of optimization in realistic quantum environments.

Reinforcement learning for quantum networks. We used reinforcement learning to optimize entanglement distribution policies in quantum repeater networks under realistic communication delays50 , showing the advantage of interpretable and locally coordinated strategies.

Quantum marginal problem and variational constraints. We investigated the quantum marginal problem in symmetric systems and its implications for variational optimization, self-testing, and nonlocality51 . The results offer structural insights into feasible marginals and global state compatibility.

Machine learning for certification. We explored how machine learning tools can assist in certifying properties of complex many-body systems, offering data-driven certificates of entanglement or local constraints52 .

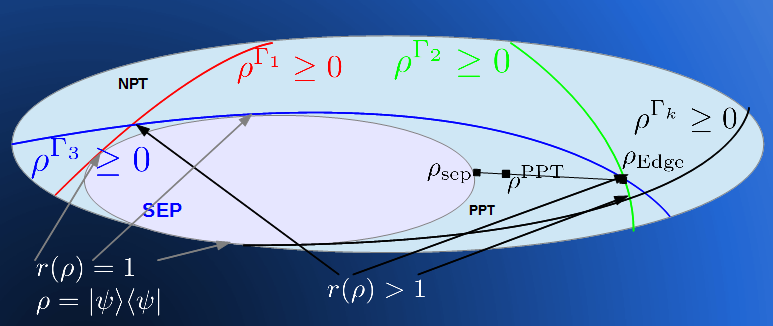

Bound entanglement in symmetric states. We demonstrated the existence of PPT entangled states in symmetric multi-qubit systems, resolving a long-standing question in quantum information theory53 54 .

Diagonal symmetric states and conic geometry. We explored the entanglement structure of diagonal symmetric states, showing that testing separability in this class is NP-hard and naturally framed as a quadratic conic optimization problem55 . Later, we established a link between these states and copositive matrices, connecting entanglement theory to non-decomposable witnesses and conic duality56 .

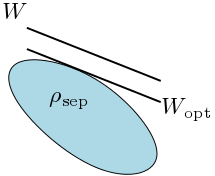

Optimality of entanglement witnesses. Our early research explored decomposable entanglement witnesses and their relation to completely entangled subspaces and unextendible product bases57 . We later applied these tools to test optimality and contributed to the disproof of the Structural Physical Approximation conjecture58 .

Entanglement vs Nonlocality. We demonstrated that entanglement and nonlocality are fundamentally inequivalent for any number of parties, highlighting the subtleties between these key concepts59 .

Structural tools for multipartite entanglement. We developed linear map techniques to certify entanglement and compatibility properties in many-body systems60 , and introduced the concept of unextendible product operator bases as a generalization of UPBs to operator spaces61 .

Foundations of quantum thermodynamics. We explored the fundamental limits of energy extraction from quantum systems, including the role of entanglement in defining passive states and their maximal energetic properties62 . This work reveals structural constraints on thermodynamic tasks at the quantum level.

Thermalization and open dynamics. We investigated the onset of thermalization in quantum many-body systems through the lens of Lindbladian dynamics and graph-theoretic techniques. Our results provide constructive bounds on convergence and thermal behavior in both classical and quantum regimes63 .

The BIG Bell Test. I actively contributed to The BIG Bell Test, a global experiment involving more than 100,000 participants to close the freedom-of-choice loophole in Bell tests by using human randomness64 . We designed both outreach material and infrastructure to integrate human choices into quantum experiments worldwide.

Science writing in IMTech. I contributed a pedagogical article on Bell correlations in quantum many-body systems to the IMTech Newsletter. This piece aims to make recent developments in nonlocality and symmetry accessible to a broad STEM audience, including undergraduate students and educators.

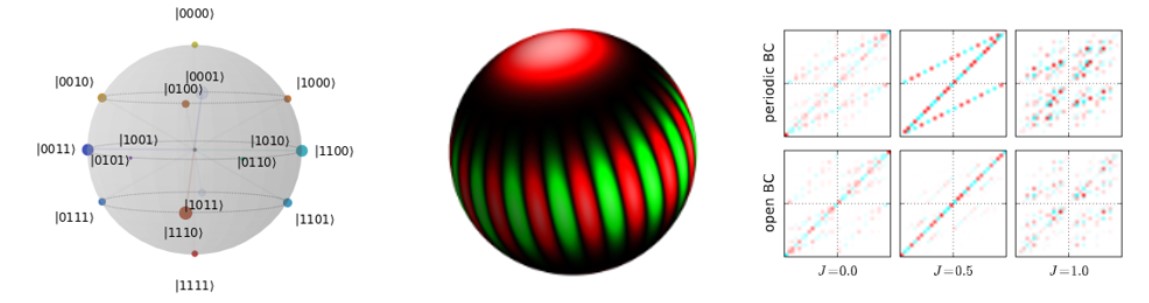

Visualizing multi-qubit states. We proposed the Bloch Sphere Binary Tree representation to visualize sets of multi-qubit pure states on a single diagram, making it easier to analyze their evolution and entanglement structure65 . The accompanying open-source Python library enables interactive use in quantum education and research.

News & Views: Insights into Quantum Computing.

Our News & Views article in Nature Physics critically examines recent experimental demonstrations claiming quantum advantage. We highlight a tensor network algorithm that challenges these claims by efficiently simulating optical quantum experiments on classical hardware66 , based on the original study.

Our Viewpoint in Physics discusses how realistic imperfections can actually simplify the classical simulation of quantum computers, potentially reducing the resources required. This insight significantly influences ongoing quantum computational research67 , based on the original research.

Our recent contribution to Nature Computational Science explores advanced parallelization techniques for tensor network contraction. This method significantly enhances the speed of classical simulations of quantum systems, thus broadening computational possibilities68 , based on the original publication.

A Christmas story about quantum teleportation. We contributed a playful piece connecting quantum teleportation to the logistics of gift delivery, using Santa Claus as a vehicle to explain key ideas in quantum communication and entanglement69 .